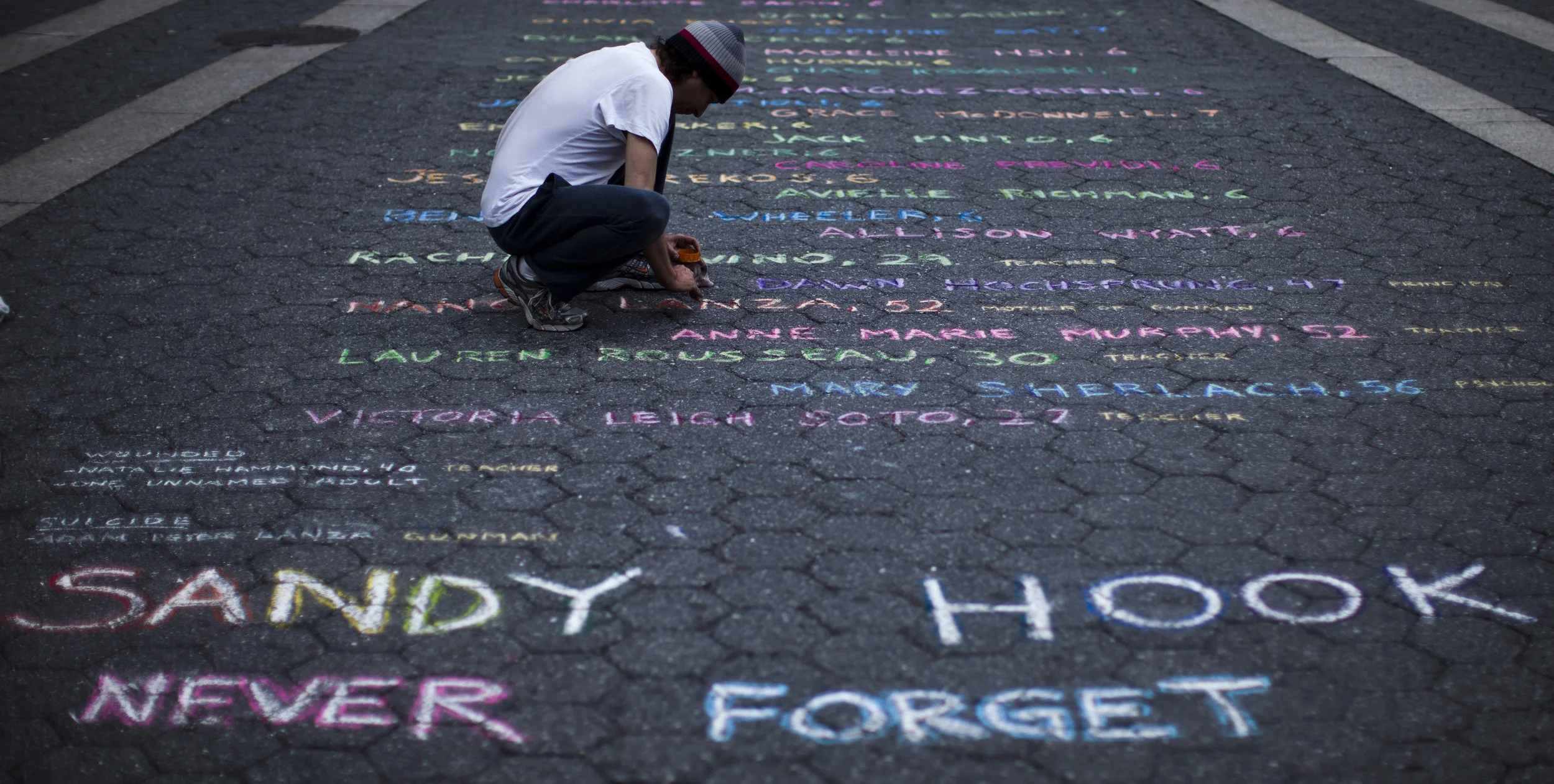

As a troubling pattern appears to have emerged, we have long felt it would be necessary to discuss the recurrent issue of mass shootings in the United States. Though there is tremendous controversy surrounding the solutions to the problem, the greater issue draws widespread concern and doubts about our nation as both a political and social entity. This week, we welcome Alex Piper to share some of his perspectives after working with Everytown for Gun Safety, as well as his opinions on the larger issue as portrayed by mass media. Are there solutions to the stalemate in dialogue? Are there cultural factors which allow for these incidents in the United States in particular? How does one cope with the tremendous emotional weight associated with such tragedies and also contribute to the larger conversation or effort?

Episode 107: Appreciating Strangers

“There are no strangers here; Only friends you haven’t yet met.”

“I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

“My fellow Americans, we are and always will be a nation of immigrants. We were strangers once, too.”

In an ever-growing and interconnected world, a glimpse outside of our social groups and inner worlds can remind each of us of the vast oceans of strangers in our world. Some consider this idea with understandable fear, but this week Olivia Sanabria joins us to help explore this conception of "the stranger". In what ways is it a mental framework with which to maintain a clear and digestible worldview? Is there are respectful and acceptable manner in which to approach those we would like to know but do not yet? What can our beliefs about those who are strangers indicate about our own perspectives and opinions? To our listeners: How do you define strangers? What is your protocol when interacting with strangers and do you tend to avoid such interactions?

Episode 106: For Non-Gamers — Gone Home

“Pick up a can of soda in Gone Home, spin it around and you’ll find a fully detailed nutrition label. Pick up anything else in the house that serves as the game’s setting and you’ll find a comparable level of detail. From the coffee mugs to the diverse styles of handwriting across every interactible piece of paper, nothing feels generic.”

“Historically games haven’t done a very good job at recreating what it’s like to inhabit a specific time and place. [Gone Home] is cut out all the things that turn the scenery into a backdrop - combat, puzzles, large worlds, etc. - and instead placed the setting in the foreground. Exploring its relatively small but astonishingly detailed manor in 1995 is the game’s central mechanic.”

This week, Phoebe Lewis returns for the second entry in our series "For Non-Gamers". She played through the critically-acclaimed success, Gone Home - a narrative exploration of a fictitious Oregonian family set in the summer of 1995. Because of her limited exposure to gaming as a pastime, we asked Phoebe about her initial impressions and discuss the similarities between the game, films and books which all contain similar storytelling elements. We also discuss the biases about gaming which this title helps disprove and how Gone Home helps model games as multimedia experiences and not as narrow entertainment. In what ways does this title illuminate first person experience as conveyed in video games? How do we conceive of the decorations and items in our houses as extensions of our families and our lives?

Further Reading:

The first episode of "For Non-Gamers"

Gone Home Website

Eurogamer, "Gone Home transports players back to 1995"

The Fullbright Company, "The Music of Gone Home!"

Game Informer, "A Home Can Hold More Than You Think"

Financial Post, "Gone Home review - A startling and unexpected storytelling triumph"

IGN, "Gone Home is Undiluted Adventure"

Episode 105: Alternative Genius

“Any intelligent fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent. It takes a touch of genius — and a lot of courage to move in the opposite direction.”

“Everyone is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.”

“The truly creative mind in any field is no more than this: A human creature born abnormally, inhumanly sensitive. To him... a touch is a blow, a sound is a noise, a misfortune is a tragedy, a joy is an ecstasy, a friend is a lover, a lover is a god, and failure is death. Add to this cruelly delicate organism the overpowering necessity to create, create, create — so that

without the creating of music or poetry or books or buildings or something of meaning, his very breath is cut off from him. He must create, must pour out creation. By some strange, unknown, inward urgency he is not really alive unless he is creating.”

Because intellectual capability is often a marker of individual value and aptitude, the title of "genius" is a highly complimentary term. But in what ways do we label others and their work as genius only to gloss over nuance and complexity as a result? Are there ways in which each of us possess genius but deny ourselves that pride in the face of more overt and compelling examples? This week we welcome Sam Graf to discuss the idea of alternative genius and it what ways in might expand our conventional definitions of genius. Are there moral components to demonstrating one's genius? Does the genius have an obligation to share their gifts and talents with their society?

Episode 104: The American Response to September 11

“On September 11, 2001, a tiny group of deluded men — members of al-Qaida, a fringe group of a fringe group with grandiose visions of its own importance — managed, again largely because of luck, to pull off a risky, if clever and carefully planned, terrorist act that became by far the most destructive in history.”

“Accordingly, it is surely time to consider that, as Russell Seitz put it in 2004, ‘9/11 could join the Trojan Horse and Pearl Harbor among stratagems so uniquely surprising that their very success precludes their repetition,’ and, accordingly, that ‘al-Qaeda’s best shot may have been exactly that.’”

Nearly fifteen years ago, members of al-Qaeda hijacked four airplanes, killing 2,996 and injuring over 6,000 in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The unprecedented tragedy of the event led many Americans, including politicians, to wonder about the likelihood of similar atrocities in the future. This week, we welcome Sam Whipple to discuss an article written in 2012 entitled "The Terrorism Delusion: America's Overwrought Response to September 11". In the article, authors John Mueller and Mark G. Stewart suggest that the political and security responses since the attacks have been blown out of proportion and imply a false probability and reality of terrorism that statistics do not reflect. In what ways do our communal fears and feelings of empathy lead us to trust in any promise of safety? How do politicians capitalize on emotion rather than facts and statistics? How might we have a healthy conversation as a country and a globe which acknowledges both legitimate fears and consistent evidence?